A Militant Dedication

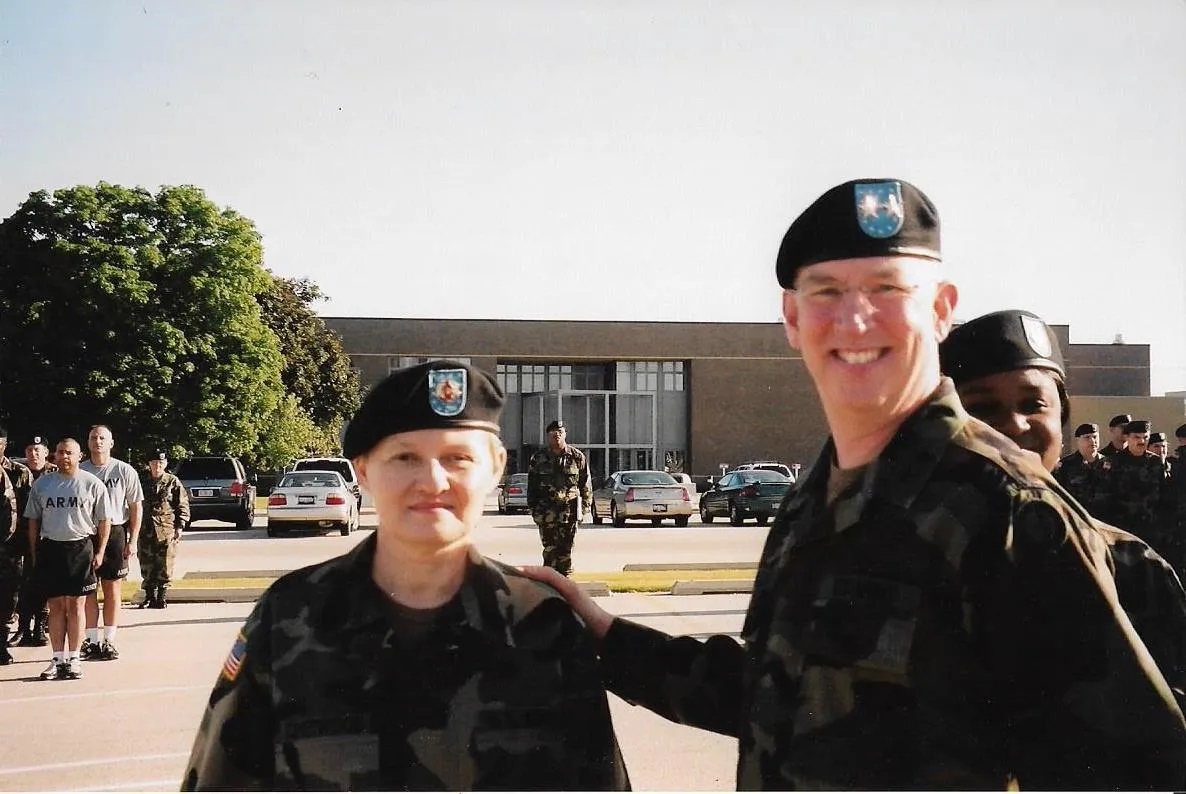

“Just to see someone in uniform makes me happy,” says Norma Chitwood, a psychotherapist at Kenosis Counseling Center in Greenwood, Indiana. “If I have a chance to say something to them, I will.”Norma has worked at Kenosis since May 2012 . She brings with her a Masters Degree in Clinical Psychology from Wheaton College and is a Licensed Mental Health Counselor (LMHC) in the State of Indiana. Her work in family crisis, relationship counseling, and mental/emotional health spans just under 2 decades and 4 different states. Among these areas of expertise, it is a longtime dedication to military members and their families that truly stands out in her professional story. This dedication stems from a distinguished career in the Armed Forces. She served in the US Army for 34 years – her journey beginning in 1974. From there, Norma served on active duty for 8 years and 4 months and spent her remaining time in the Army Reserves where she served two active duty tours. She was assigned to the Stabilizing Forces (SFOR) stationed in Bosnia in 1997 and served over 5 years for Operation Enduring Freedom during the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts. She eventually reached the rank of sergeant major – the highest you can go in the enlisted ranks of the US Army. “I love talking about the military,” she says with a laugh.

You Just Love Soldiers

This background instilled a personal and professional passion to work with military members and their families. She is a STAR Behavioral Health Provider and a certified Military OneSource Provider through the Department of Defense. With these certifications, she treats current and former service members experiencing reunion issues, marital issues, marital discord, children of military members, and general phase of life problems for soldiers and their families. She also helps military members work through mild trauma, anxiety, hypervigilance, anger, and other mental/emotional issues experienced in response to their service.“I think for most people who reached the rank that I did, you just love soldiers,” she says on why she does what she does. “I’m not quite sure how to explain it, but you have a passion to want to help them. Whatever you are capable of providing you want to provide.”In providing what she can, Norma continues to serve the military on the home front. She joins the millions of professionals dedicated to helping soldiers and their families re-adjust to civilian life – a mission that has had its share of ups, downs, and advancements in recent decades.

The Current State of Reentry

A study published by the Pew Research Center in 2011 revealed some concerning statistics. Regarding post 9/11 veterans and their families, 55% of combat veterans and 38% of non-combat veterans experienced strain in family relationships after deployment. In addition, post 9/11 veterans who had young children during active duty were more likely to report strains in family relations since returning home (57% combat vs. 43% non-combat). “These families do experience difficulty during different phases,” notes Norma on the relationship strains experienced after redeployment. “It may not be immediately because that reunion can initially be very happy – but over a period of time, depending on what the military member endured, what kind of trauma they were exposed to – some of the symptoms and emotional problems can creep up even 6 months or sometimes longer, later on after they’ve redeployed.” In response, the military has stepped up reentry support services in recent years. Military OneSource – which Norma is a provider for – covers 12 counseling sessions for military members and their families upon their return home; in some cases, this coverage can extend to more sessions depending on the needs of the service member and their family. Another successful program is Strong Bonds, a retreat service established in 2003 that facilitates reunification and communication skills training for single or married military members and their families. Retreat events are fully covered and often hosted in luxury hotels around the US. During her time in the military, Norma personally assisted in the training of these events and notes their success.

“I saw married couples walking in on Friday night appearing distant, not sitting too close together, and then walking out hand-in-hand on Sunday afternoon,” she says.

Reentry and Relationships

The creation of these services marks a turning point in military reentry support (since 9/11) that is hopeful to Norma. They signal the military’s recognition of the role of family in mental health – a recognition arguably lacking in previous wars and decades. But desires to improve are providing new conceptions of support – ones that target the wellbeing of the home life and a mission to maintain these vital relationships.

“The family is part of it. If there is something happening at the home front, that’s not good. And those families – marital discord, problems with children – that’s going to affect his or her work on the job, and that’s going to affect the overall military mission,” she says. “The military (and those in leadership roles) have missions that need to be accomplished, and they don’t want anything negatively impacting it. If a military member is going through difficulty because of family issues, we need to nip that in the bud – we want to deal with that.” This is where Norma comes in. Thanks to her expertise in mental health and her personal background in military service, she – and other professionals like her – play an integral role in bridging the reentry gap for military members. They provide the one-on-one support needed in healing emotional issues experienced post deployment. In doing so, they ease the reentry process for military members and help maintain these critical home life relationships.

Hypervigilance

To provide successful emotional support, Norma must first identify the interfering cause – and one of the most common inferences she sees is hypervigilance. Hypervigilance is a state of “increased alertness” and a heightened sensitivity to one’s surroundings. This makes returning military members feel aware of hidden dangers in their environment – dangers that, although very real during service, are no longer real in their civilian lives.“This is something I experienced myself, I have to confess,” she says, referring to her own reentry experiences. “Some of the training that the United States Army gives – they train you to be that way in a combat situation, and wherever you go to some degree. Anything unusual, you need to be careful, you need to always be on your guard – that (idea) was drilled into our heads.”Hypervigilance manifests in the most ordinary of civilian situations such as in crowds or eating out at a restaurant. Norma has had patients tell of dining out and insisting they be the first to enter a room and sit at tables with a full view of the restaurant. She even mentions a woman who told off two customers at a deli; the customers were guilty of a common practice – briefly leaving a bag unattended while they stood in line to order food. “For folks who have not experienced what they’ve experienced (it’s not an issue),” she says, “but for (military members), it’s a big deal – someone just leaving something (unattended) like that.”In addition, hypervigilance can be triggered by sounds such as traffic noises or firework celebrations during the 4th of July. “A car backfiring or a loud explosion can all cause heightened anxieties and (behavioral) overreactions,” she says.

Anger

Another common emotional issue Norma has seen – both in her practice and in her own military career – is anger. “I encountered military members who came back extremely angry, irritable, some level of depression – just a lot of anger, a lot of hatred. This would interfere with their relationships and people around them,” she explains. “I remember one of the reasons military members struggled with anger so much was because of superiors who didn’t get along with them. You’re with these people day after day in a combat situation and they are your family. If there’s personality conflict with those who outrank you – that can be a very difficult situation to deal with on a daily basis.” She explains that this anger can be so deep and extreme that it can prompt military members to do things they never thought they would do under normal circumstances.” One time, we had a high ranking soldier actually pull a gun on his commander when he was in Iraq. Just from an overreaction – a misunderstanding,” she says, referring to a situation during her time as a sergeant major. “Just the differences with struggles concerning different personalities – that really was difficult for many military members, and they can come back emotionally wounded from that.”

A Unique Relatability

“In this civilian world in which I see them, people might not understand those issues or what they are going through,” says Norma referring to the emotional and relational struggles of military reentry, “but (because of my own military background), I do.” Norma continuously draws upon this relatability in her practice, offering military patients a unique perspective that other counseling professionals in her niche may not possess. “I do have some understanding, and I like to show military members that there is someone else out here who understands and can relate to what they are going through,” says Norma, “I may not fully understand at the level of depression or anxiety, but I have an understanding of being a soldier, and also my mental health training helps me have an understanding of where they are coming from in relation to their mental and emotional health.”

She hopes this combined military background and mental health training can reach military members struggling to talk with those who have never been in the reserves or deployed overseas.

The Future of Support

Norma hopes that the future of reentry includes better support services for military members (and their families) stationed in the army reserves. Sometimes called “weekend warriors”, she explains the unique challenges of reentry for these part-time soldiers working closer to home. “The family support and mental health resources are lacking (when it comes to the reserves), they don’t get the attention that active duty military members would get. Oftentimes an active duty member is on a military institution and their spouses and families are there and they have that support right there. But a reserve soldier goes back and forth to their civilian area, and they don’t have those resources available, nor do their family members,” she says. In other words, army reserve individuals may not experience direct combat, but they do experience the rigorous training and ranking environment that can cause hypervigilance and anger issues discussed above. This can potentially compromise the relationships in their civilian life – relationships they return to more frequently than their active duty counterparts. “Because I was in the active army, I was also in the reserves, and I have a passion for them and the struggles that they have. They’re out here in the civilian world and they’re away from their comrades and colleagues where they might see them once a month when they (attend trainings),” she says. Norma does note that the 12 counseling sessions provided through Military OneSource includes the reserves, but she hopes even more will be done to target the unique emotional and relational challenges faced by these military members and their families.

Always Have, Always Will

No matter what the future of military reentry may hold, Norma’s dedication to the cause remains steadfast. Since first stepping into a recruitment office in 1974, to reaching the rank of sergeant major, to her transition to support services and fulltime mental health – the military has always been, and will always be, a passionate focus in her working life. “I’ve always had a passion for the military,” she says, “Always have – always will for as long as I live.”